We invited Nick Hood, head of external affairs with Company Watch, to analyse the figures to see who have been the winners over the past 12 months, who has been less fortunate, and how the UK’s leading contractors are performing.

A year ago, construction industry pundits were cautiously celebrating the first tentative signs of recovery after the long downturn provoked by the global financial crisis. Since then all the news has been positive in terms of growth in activity levels, most notably for those companies servicing the rip-roaring success of the British housing market.

Despite this, our survey of the financial results of the Top 100 contractors repeats the stark message we delivered last year; revenues are static, profit margins are pathetically small. Prospects remain uncertain because of ongoing downward pressure on contract pricing from savage competition and because of the twin evils of skill shortages and rapidly rising input costs.

The financial statements we have analysed mainly cover trading for part of 2012 and most of 2013, so it may be that the fruits of the sector’s recovery are yet to be seen. Contracting is a long-term business after all, so expansion takes time to translate into higher profits and even longer to be converted into cash or to reduce debts. Even so, it was disturbing to see two of Europe’s construction giants, Balfour Beatty and Royal BAM Group both rush out profit warnings on the same day towards the end of last month. Both were forced to report that they were doing no better than break even.

A year ago, we dashed hopes that the 2012 Olympics might have delivered a profits bonanza for the leading contractors, reporting static turnover and falling profit numbers. Not much seems to have changed as the industry has moved on from that distraction and sought to maximise the benefits to be had from the promised surge in infrastructure spending and the general economic upturn. Turnover is still stalled, but while profits have moved up, the improvement is marginal. The overwhelming impression is one of stagnation in performance terms.

In overall terms, the Top 100 had total revenues of £58.4bn, an increase of just 0.7% since last year. Total profits were £872m, up 10.5% from £789m last time round. The average profit margin rose very slightly from 1.36% to 1.49%, but this remains pitifully thin at a time of rising costs, which even the biggest players are clearly finding difficult to pass on to their clients.

Excluding the loss figures for Lakeside/Keepmoat for this year (£21m) and last year (£473m), the true scale of profit shrinkage among the remaining 99 companies becomes clear. The revised totals show total revenues of £57.5bn (up only 0.3%) and total profits of £893m, a drop of over 29% on last year’s adjusted £1.26bn. The profit margin has therefore fallen from 2.2% last year to 1.55% now, a similar fall of 29%.

The raised business risk in this sort of financial profile is well illustrated by the fact that these construction leviathans are deploying total assets of £33.6bn, have a combined net worth of £8.6bn and are carrying debts of £4.1bn. That makes a return of just 2.65% on total assets and 10.4% on capital employed. This compares with 3.6% and 13.3% last year - an improvement but hardly cause for dancing in the streets.

It must be remembered that these are supposedly the most efficient operators in the sector, with the greatest bargaining power on bidding prices and input costs. This poses real questions about the validity of the entire UK construction business model. If they are struggling to make a sensible profit, what chance is there for the poor bloody infantry, the tens of thousands of smaller businesses lower down the construction food chain?

The best profit margins were earned by a top five of Dawnus (9.7%), Bechtel (9.1%), RJ McLeod (7.7%), Thomas Armstrong (6.8%) and Mullaley (6.3%). The risers and fallers were more evenly spread this year; 43 had better margins, but 56 had worse despite the overall marginal improvement.

A continuation of this trend through the rest of 2014 and into 2015 may cause casualties amongst our sample. The capacity of the traditional funding market remains constrained, while cautious lenders do not have limitless patience with marginally profitable or loss-making borrowers.

The Balfour Beatty/Carillion merger saga and some other consolidation activity amongst the industry leaders (with deals such as the combination of Kier Group with May Gurney and of Amey with Enterprise) demonstrates the pressures on under-achievers. But deals in the short and medium term within the sector are more likely to be acquisitions of mid-market UK players by bigger rivals, either domestic or international.

There have been no failures among the Top 100 in the past year (unlike the situation we reported last autumn) and insolvency statistics for construction businesses continue to fall both in absolute terms and as a percentage of all UK failures. (On page 39 of this issue there is a more detailed analysis by turnaround experts Opus Restructuring which includes comments on how insolvency methodology is changing and how it might impact on the construction sector.)

Within the Top 100, there has been considerable movement in relative performance. Forty-four companies improved their turnover ranking while 42 dropped down the league. The biggest companies have largely held their positions, with the major gainers found lower down the table.

Lakehouse Contractors is the biggest winner, jumping 14 places to 55th, followed by Dawnus (up 11 places), Lagan (also 11), Brookfield Mulitplex (10) and T Clarke (also 10). The losers are led by RGCM, which drops 19 places to 68th and Barr, down another 17 places to 52nd. Other major fallers are GSH Group (16 places), Spie Matthew Hall (also 16) and Winvic (11).

Keeping in mind the old business cliché that ‘top line is vanity but bottom line is sanity’, we notice much more volatility in the profit tables. This reflects the commercial reality that fortunes can change rapidly, quite often as the result of the outcomes on a limited number of successful or, conversely, problematic contracts.

Some of the changes are striking: 57 companies improved their ranking and 41 slipped lower. Geoffrey Osborne is the highest climber, up 46 places to 43rd. Other major risers are McNicholas Construction (up 35), Sisk (34), Barr (33) and GSH Group (27). The biggest faller is Bouygues, which has fallen 82 places to 97th.

Other significant changes are Lend Lease (down 72), NG Bailey (59), Emcor (also down 59) and Mabey (54).

Just as last year, 15% of the Top 100 have fallen down the turnover rankings, but risen in terms of relative profitability. This suggests that the strategy of eliminating marginal or loss –making activities is well entrenched, recognising that this continues to be no time for being busy fools.

Last year 16 companies slipped down the profit rankings whilst simultaneously climbing the turnover league table. This year fewer companies have seen profits fall significantly while turnover increased. And, with the exception of Forth Holdings which jumped six places, the turnover gain was marginal, being only one or two places and thus not significant. This is a welcome turnaround.

So which contractors have had the best year since our last report? Once again, as if to drive home the message that big is not necessarily beautiful, this prize eludes our biggest firm, Balfour Beatty. Last year its profits fell by 70%, this time the fall is 57% and, as we know, it is now battling to break even. Nor is Interserve the winner, with profits tumbling 62% from £180m to £68m. Interestingly, six of the 10 largest contractors dropped down the profit rankings, five of them after substantial profit reductions.

Carillion, the rejected suitor for Balfour Beatty, made the biggest profit at £111m, followed by the Amey/Enterprise combination which declared a figure of £79m. Curiously, last year's least profitable company, Lakeside/Keepmoat, actually slashed its losses by 95% to £21m.

Looking across all the key measures, Miller was the most consistently successful among the bigger contractors. It not only grew profits by 57.6%, but rose 12 places up the profit league and four for its turnover, which grew by 32%. Its profit margins improved by a healthy 20%.

Among the smaller companies, honourable mentions must go to Lakehouse (profit up 48%), Dawnus (+41%) and Malcolm Group (+33%), but the clear winner was Lagan with a 211% profit gain and league table rises

of 19 and 11 for profit and turnover respectively. Its turnover was 36% higher and margins were up by 130%.

There has been little movement in the constituents of the Top 100. A few companies have been removed since last year because a closer review of the entry criteria excluded them this time round. The Amey/Enterprise grouping removed another. Altogether there are five new entrants, the highest being Pyper Construction in 77th place.

The last consideration is where construction is headed over the next twelve months. The talk is all of rising activity, tempered by concerns over skill scarcity, supply chain bottlenecks and rising material costs.

Output in June 2014 was 5.3% higher year-on-year and 1.2% higher than in May according to the Office for National Statistics, but overall Q2 2014 showed no growth over Q1 2014, suggesting that growth has levelled off after a period of sustained improvement.

In contrast, the Markit/CIPS Construction PMI for July showed the strongest cyclical upswing since the start of the global financial crisis in 2008, but much of this can be accounted for by the extraordinary growth in house-building. The Construction Products Association has just predicted a 10% expansion for the construction industry by the end of 2016.

‘You pays your money and you takes your choice’ as they say; prospects look good for growth, but will profits be similarly suffused by the rosy glow of growth? Will supply chains hold together under the sustained pressure every pundit and expert is reporting? The 2015 Top 100 table will reveal all and we look forward to picking out the highlights again this time next year.

How’s your health?

Never mind the profits, look closely at the balance sheet

Whatever profits are disclosed, this is only one aspect of a company’s financial affairs. The real issues are lurking in the balance sheet and this is where the serious attention should be focused.

An established method for judging the financial health and strength of a business is to look at seven key financial ratios and the interaction between them. One of them is profitability, but there are three more involving how the company is funded and another three concerned with its asset profile. Blend them all together, apply some mathematical algorithms and out pops a financial health score: the Company Watch “H-Score”, expressed as a score out of a maximum of 100.

Companies with an H-Score above 75 are in rude health. A score between 50 and 75 is fair-to-middling. Any H-Score below 50 looks a bit off-colour and a business with an H-Score of 25 or less is in the Company Watch “warning area”. Over the past 16 years, one in four of the companies in this ‘red zone’ has gone on to either file for insolvency or undergo a major restructuring.

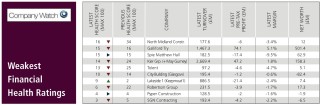

Company Watch ran the financial rule over the Top 100 construction companies to see how they measured up. At the top of the league are just seven companies with a score of 76 or more. This is down from 10 a year ago.

All but one of them have profit margins well above the average of 1.49% for the Top 100 and four of them earn more than 5% on turnover. They are far from the largest by turnover, suggesting that smaller may be more beautiful. In fact the four largest companies by turnover all rank in the bottom third when measured by their H-Score.

The best score is the 180-year-old Cumbria-based Thomas Armstrong Group which again scores 91 out of 100, just as it did last year. It makes a margin of 6.84% and is both asset- and cash-rich, with bountiful working capital. The second strongest is another privately-owned contractor, Essex-based Mullaley. Its rating is 82 out of 100, influenced by profit margins of over 6% and a strong working capital position.

At the bottom of the league are 18 companies in the warning area with scores of 25 or less, half of them loss-making. Last year there were 19 in the red zone. As well as losses, adverse factors include high levels of debt, abnormally high inventory lock up and marginal or negative net worth positions.

The clear message from the analysis is that the Top 100 construction companies are certainly the largest in the sector in terms of turnover, but the most mixed of bags when it comes to their overall financial health.

Rather worryingly, their average H-Score has dipped in the past year from 48 to 46, the second year running this measure has fallen. It puts them a little below the average for the whole economy for companies of this size, suggesting that, in terms of business efficiency, the construction industry in under-performing and has a lot of catching up to do.

The Company Watch analysis throws some interesting light on construction companies that might be generally perceived as strong.

Galliford Try, for example, which acquired Miller Construction earlier this year, recently reported record profits of £95.2m before tax for the year to 30 June 2014. This figure was up 28% on the previous year’s £74.1m. Annual revenue was also up strongly, by 21% to £1,768m (2013: £1,467m.) However, Company Watch gives it a perilously low Health Score of just 15, down from 16 last year.

Nick Hood explains that Galliford Try has low liquidity: ‘quick’ assets (debtors and cash) were £555m in the accounts analysed, compared to current liabilities of £816m, leaving a shortfall of £261m as against an annual running rate for expense outgoings of £1.7bn.

Coupled with this, Galliford Try has high inventory: 48% of sales & 159% of net worth in the latest accounts. While this is to some extent the business model for companies dominated by house-building, other major players have more strongly compensating strengths in their balance sheets.

Kier, which acquired May Gurney last year, is in even more financial danger, with a score of 14, down from 24 last year. Issues here include intangible assets of 105% of net worth, meaning that it has a deficit of tangible assets, which Company Watch views as a negative characteristic. Gross debt is 104% of net worth, which is not exceptionally high but beyond normal parameters, hence a drag on the overall health score.

Kier's accounts also show working capital to be thin, at just £109m against sales of £3bn. Liquidity is low: there were ‘quick’ assets (debtors & cash) of £649m versus current liabilities of £1bn (a shortfall of £351m) in the context of expenditures of £2.9bn as per the latest accounts.

Finally, also counting against Kier is that it pays out a high percentage of post-tax profits in dividends. The ratio was 63% in 2012/13 and 348% in 2013/14.

On discovering this, should we no longer consider it a coincidence that both Kier and Galliford Try have recently or will soon change leadership? Kier chief executive Paul Sheffield stepped down this year, to be replaced by the finance director, while Galliford Try chief Greg Fitzgerald has also announced his intention to step down in the coming months. Both men are way off retirement age; Sheffield was 52 when he left and Fitzgerald is just 50.

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in the September 2014 issue of The Construction Index magazine. You can read the full issue online at: http://epublishing.theconstructionindex.co.uk/magazine/september2014 To receive your own printed copy every month, in traditional paper format, you can subscribe by going to http://www.theconstructionindex.co.uk/magazine and scrolling donw the page or dialling 0845 128 9700 on a telephone.Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk