What with a close call in the Scottish referendum and who-knows-what to come in the EU referendum, it seems a lot of people fancy having a bit more independence these days. The English are no exception; devolution is a fashionable idea, with all major political parties approving of the idea. In fact, it’s already happening.

Devolution in England is supposed to bring local control over budgets for infrastructure, housebuilding planned across wide areas, easier use of spare public land for development and all with extra money available.

Sounds too good to be true for developers and builders? Well, Greater Manchester is racing ahead with its devolved combined authority and, after a few false starts, Merseyside, South Yorkshire, Tees Valley and the West Midlands have now got their acts together.

In these areas the industry can, at least in theory, look forward to more rapid infrastructure provision as projects will not have to go through the arcane machinations of Whitehall to gain approval - decisions will be taken locally.

Elsewhere though, devolution has either not started or is mired in obscure disputes between councils.

Outside England’s conurbations, Cornwall and Lincolnshire have secured devolution agreements with the government - useful for them but perhaps not places likely to host a great deal of construction activity - and one is being negotiated for Bristol, Bath and the surrounding area.

These tentative moves towards devolution represent a brave step for local authorities, which could perhaps do with some encouragement from the private sector. Just telling them to “hurry up and get on with it” is unlikely to work, but it would certainly help if private investors outlined some of the opportunities for infrastructure development and job creation that await a regional government with sufficient power devolved to it.

It all began in Greater Manchester, where the 10 boroughs have a long history of collaboration. Their request for devolved powers found a sympathetic ear in chancellor George Osborne who, depending on one’s view, either genuinely believes that devolving power will better drive economic growth or sees a splendid opportunity to make local authorities responsible for potentially unpopular measures.

Devolution works by Whitehall ceding certain powers to groups of councils which form a combined authority to exercise these powers. Each individual council carries on as normal with planning, building control, highways maintenance and its other responsibilities.

The new powers devolved to Greater Manchester include control over a long-term budget to improve the transport network, additional planning powers to encourage regeneration and development, £300m to build 15,000 new homes over 10 years and an ‘earn back’ fund under which councils get extra money from sharing in the economic growth they help to create.

There are in addition other devolved powers related to health, social care and skills training.

Other conurbations looked at Manchester with envy and wanted something similar. But they had a problem: no-one disputed where Greater Manchester’s boundary was; elsewhere this issue would bedevil progress.

Merseyside’s boundaries were relatively straightforward - Halton, Knowsley, Liverpool, Sefton, St Helen’s and Wirral - but suspicion among the other wards of dominance by Liverpool caused delays.

The area now has a devolution deal with a consolidated local transport budget, powers over strategic planning, an assets board to find surplus public land and enable its development and a £30m-a-year budget for 30 years to unlock the economic potential of the River Mersey and its Superport and maximise the opportunities from HS2. Again, there are other powers not directly concerning construction.

Deals offered for South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, Tees Valley, the North East and West Midlands were similar, most of them also including the £30m-a-year budget too.

All these deals, though, have involved creating the role of an elected mayor to oversee the exercise of devolved powers. This has led to concern about creating another layer of local government and about the wisdom of giving one person effective control over such vast budgets and areas.

The North East got a deal agreed, only for Gateshead to drop out citing concerns over the mayor issue and whether enough government funding was on offer. Durham and South Tyneside then postponed decisions on joining, putting the whole project into question.

West Yorkshire did secure a limited devolution deal but it wanted the whole Leeds city region included, which takes in the district councils of Craven, Harrogate and Selby.

North Yorkshire County Council is the highways and transport authority for this trio and objected to handing over these powers.

This caused an intractable dispute. Without the highways powers, the combined authority could not sensibly plan for transport and infrastructure; but handing the powers over would leave North Yorkshire an oddly-shaped, wholly rural and much-diminished council. There, for the moment, matters rest.

The West Midlands eventually got a devolution deal covering its heartland of Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall and Wolverhampton together with a rather random collection of adjacent districts, including Tamworth and Redditch but excluding urban centres like Bromsgrove and Rugby, which decided against joining.

This followed tortuous negotiations about whether Coventry would join and, if it did, what would happen to Warwickshire, with which it had been in an economic partnership. Parts of Warwickshire have joined the West Midlands Combined Authority and others not.

Nor is it obvious how Staffordshire will fit into devolution, as only its Cannock Chase and Tamworth districts have joined West Midlands.

There has been equal silence from Shropshire on devolution although Telford & Wrekin has joined the West Midlands Combined Authority despite lacking a common boundary. The final shape of who joins what in Worcestershire remains a matter for conjecture.

Perhaps the most spectacular collapse of a devolution deal so far has been Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. The two county councils, the 15 districts within them and the unitary city councils of Derby and Nottingham had all asked the government for devolved powers over planning, transport, economic development and other matters.

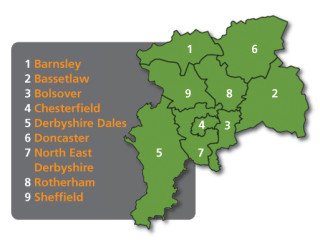

When asked to formally sign, Amber Valley, Erewash and South Derbyshire councils dropped out citing concerns over mayors and money. High Peak decided it should try for associate status with Greater Manchester, while Bassetlaw and Chesterfield opted instead to join Sheffield city region’s devolution deal, based on South Yorkshire. The remaining 13 councils insist they will persevere with seeking a deal.

East Anglia likewise seemed on the brink of a deal but the government insisted that Cambridgeshire and Peterborough should join with Norfolk and Suffolk.

Cambridge is an economic powerhouse, driven by its university and science-based economy and with huge housing pressures resulting in some of the highest prices outside London.

The city council refused to endorse the deal, fearing the huge area involved meant the money would flow to deprived communities like Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth rather than Cambridge. Cambridgeshire County Council then also raised a string of objections, leaving the whole thing in doubt.

In Essex and Hampshire, devolution has been beset by rows over whether agreements should cover the whole county. Tensions have arisen because the south of both counties is urban while the rest is mainly rural.

Portsmouth and Southampton city councils, the districts around them and the Isle of Wight now think they are close to a devolution deal for their conurbation focussed on transport infrastructure and housing. This has infuriated Hampshire County Council, which finds itself being effectively cut in half.

Along the north bank of the Thames, Southend-on-Sea, Castle Point, Basildon and Thurrock see themselves as an urban area needing a bespoke devolution deal separate from anything done for Essex’s rural north (private references to “people in smocks” suggest relations are not good).

Do these baffling disputes between local politicians matter?

Well, yes, because devolution could unlock a lot of spending on infrastructure and homes. Home Builders Federation policy director David O’Leary says: “There are pros and cons but on balance devolution is a benefit to the industry because most of the agreements talk about speeding up housing delivery.”

O’Leary said the asset boards that feature in several deals “could be very useful if they can really sort out surplus land and if there is then something there that makes that ready for development. There is huge potential there.”

He also thinks that working in a combined authority may improve the duty to cooperate on local planning where this has not worked well, since devolution requires councils to collaborate.

A British Property Federation spokeswoman says: “Clearly there is a real drive from government for this but there will be lessons to be learnt. Deep negative relationships that exist in some places are not going to be solved by a photo opportunity.

“Devolution will be beneficial for the property industry with more local decisions on planning and infrastructure but there is no fixed defined way to do things.”

Matthew Lugg, director of public services at consultant Mouchel and formerly highways director for Leicestershire County Council, thinks the success of devolution is important to construction because “this is clearly the government’s chosen way to encourage growth in the economy, so it’s a bit of a no brainer”.

He says that places with a history of collaboration between councils have inevitably found devolution to combined authorities easier to implement than others.

“Where there is a clear identity it makes more sense,” Lugg says. “Where there isn’t, and councils could go any of several ways, is where you have problems.” Joining up areas is difficult where it cuts across the political geography and local authorities should not be blamed for problems, they need some help.”

Devolution could see money flowing into housebuilding and infrastructure based on plans founded on wide agreement. In some places it’s happening, but to spread across England is going to take a while.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk