When Boris Johnson’s 2019 general election manifesto promised the construction of 40 new hospitals by 2030, it sounded too good to be true. Now, thanks to a National Audit Office report published in July, we know that it was.

That said, there’s still a lot going on and plenty more coming down the tracks.

Hospital construction has become as much a political hornet’s nest as the state of the National Health Service itself. In the 1990s and early part of the 21st century it was tied up in the controversy surrounding the buy-now-pay-later confidence trick that was the private finance initiative (PFI).

Then came the collapse of Carillion, leaving the new Liverpool Royal and Midland Metropolitan hospitals unfinished. The Liverpool Royal finally opened, in October 2022, five years late and more than nine years after construction started. The Midland Met, where work started on site in January 2016, is expected to open in 2024. The interruption of the Covid-19 pandemic did not help.

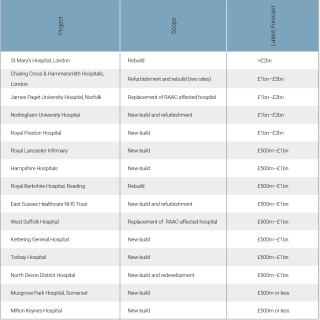

The Department of Health & Social Care (DHSC) published a Health Infrastructure Plan (HIP) in September 2019 to modernise the NHS estate. Initially it listed 27 new hospital schemes to be completed by 2030 but in October 2020 the list was expanded and 40 new hospitals were promised for 2030.

The HIP identified and provided information on the types of improvements at 32 of these new hospitals, while another eight would be selected later. Alongside eight other hospitals that DHSC had already approved for construction, and which it was not counting towards the 40 new hospitals commitment, this meant a total portfolio of 48 hospital schemes by 2030.

The schemes were subsequently split into five cohorts based on programme and priority, and DHSC set up the New Hospital Programme (NHP) to deliver them. The programme was also tasked with improving efficiency, quality and standardisation in hospital construction – using prefabrication of modular components – and a centralised approach to contracting.

It soon emerged that most of these ‘new hospitals’ were in fact extensions and/or refurbishments of existing hospitals. Substantial and much needed improvements, no doubt, but presented to the electorate in a way that was deliberately politically misleading.

July’s National Audit Office (NAO) report details that only 11 of the schemes are actually complete hospitals.

The NAO also exposes a lack of transparency in the decision-making process governing which schemes are brought forward, implying that some hospitals have been advanced on the basis of political, rather than health, priorities. It recommended that future hospital construction projects should be chosen more transparently, with full records kept.

“Responding to NAO requests, DHSC was unable to document the process originally used to select HIP schemes,” the report says. “DHSC, supported by NHS England, used evidence-based criteria to create a shortlist but then adjusted this shortlist substantially, a part of the process for which no further documentation is available. The failure to document this part of the process is an omission which means there is no basis for the NAO to determine why DHSC selected these schemes. For large capital programmes, the NAO expects government to use clear, defensible criteria to select schemes and to maintain records of its decisions.”

In 2020, DHSC estimated it needed between £19.8bn and £29.7bn of capital funding to build those 48 hospitals by 2030. This included between £3.7bn and £16bn for the programme’s first four years up to 2024-25.

HM Treasury’s decision in the 2020 Spending Review to provide £3.7bn up to 2024-25 meant most of the larger hospital schemes would need to be delivered towards the end of the decade. In its options appraisal, DHSC labelled this “maximum risk and policy compromises”.

This approach would likely result in many schemes being simultaneously under construction, making it harder to find builders and potentially increasing costs, the NAO said.

To date, the NAO said, the government has spent £1.1bn on the programme, is making “slower than expected” progress and “has not achieved good value for money”.

It advised: “It can improve value for money through to 2030 but needs to manage substantial risks, including the risk of building hospitals that are too small and rising costs resulting from hospitals being built simultaneously.”

Assessing progress is made trickier by perpetual changes to the programme.

DHSC reset the programme in May 2023 after the risks associated with crumbling reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) came to be better understood. Five hospitals constructed mostly using RAAC were urgently added to the front-end of the programme, as a new ‘fifth cohort’ to be built – or rather re-built – by 2030 while eight were pushed down the list and will not now be completed by 2030, as had been originally promised.

The NAO concluded: “By our analysis, this means that DHSC’s plans will now lead to 32 new hospitals by 2030, according to the definition it used in 2020.”

The five RAAC hospitals are Airedale in West Yorkshire, Queen Elizabeth King’s Lynn in Norfolk, Hinchingbrooke in Cambridgeshire, Mid Cheshire Leighton in Cheshire and Frimley Park in Surrey. It may or may not be a coincidence that all are in Conservative-held constituencies.

These five are in addition to two of the worst affected hospitals – West Suffolk Hospital in Bury St Edmunds and James Paget Hospital in Norfolk – which were, and remain, in cohort 4.

The NAO noted that forecast costs for schemes in cohorts 1 and 2 increased by 41% between 2020 and 2023. In 2020, NHP was allocated £2.0bn for cohort 1 schemes but by March 2023 their forecast cost had grown to £2.7bn. Similarly, the allocation for cohort 2 schemes was £916m in 2020 but by March 2023 the forecast cost was £1.3bn. The cost increases were attributed to higher-than‑expected inflation and under-estimation of costs by some NHS trusts.

“Additionally, for reasons that are unclear,” the NAO said, “DHSC had not budgeted for essential elements of two of the schemes: the Royal Liverpool University Hospital and Brighton 3Ts schemes are now forecast to cost some £400m more than it expected.”

The New Hospital Programme is trying to get control of costs by producing a standardised hospital design – dubbed Hospital 2.0 – based on modular components. The plan is to use this for schemes in cohort 3 and later. For cohort 4 schemes, hospital construction will be 20% quicker and 25% cheaper than the traditional approach, the government predicts. The NAO acknowledges that standardisation can bring efficiencies but says that “NHP still needs to demonstrate that this level of efficiency is achievable”.

Furthermore, the creation of Hospital 2.0 is itself running behind schedule. There have been shortages of technical staff, the NAO reported, and it will not now be completed until May 2024. The delays have constrained NHP’s ability to engage with industry, it added.

“Until Hospital 2.0 is finished there are limits to NHP’s ability to make progress with planning schemes in cohort 3 and later,” the NAO said.

Furthermore, the NAO found that NHP’s “minimum viable product” version of Hospital 2.0, which is intended to achieve key objectives at the lowest possible cost, may result in hospitals that are too small. This is because NHP is modelling hospital sizes using out-of-date assumptions, including dependence on wards rather than single rooms.

In his summary, Gareth Davies, the head of the NAO, said: “The programme has innovative plans to standardise hospital construction, delivering efficiencies and quality improvements. However, by the definition the government used in 2020 it will now deliver 32 rather than 40 new hospitals by 2030.

“Delivery so far has been slower than expected, both on individual schemes and in developing the Hospital 2.0 template, which has delayed programme funding decisions.

“There are some important lessons to be drawn for major programmes from the experience of the New Hospital Programme so far. These include strengthening the business case process to improve confidence on affordability and delivery dates and improving transparency for key decisions.”

On top of all this, the poor old NHS also has a £10.2bn backlog in estate maintenance work. While we are failing to build new facilities quickly enough, the facilities we have are falling apart for lack of upkeep.

Meg Hillier MP, chair of the House of Commons public accounts committee, said: “English hospitals are in poor condition, after years of underinvestment. The NAO report shows government’s woeful lack of progress against its commitment to build 40 new hospitals by 2030. It has failed to even begin construction on any of the new hospitals in its second cohort which it thought were quick wins.

“The Department of Health & Social Care has been trying to move the goal posts so it can claim it has met its target. Patients and clinicians are going to have to wait much longer than they expected before their new hospitals are completed.”

The New Hospital Programme

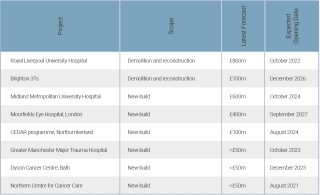

Cohort 1

Eight schemes: two are complete, five in construction and one (Moorfields) under design. All are forecast to be complete by the end of 2027.

Cohort 2

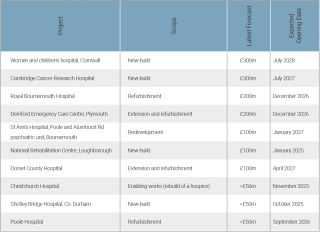

Ten schemes expected to complete by early 2028. All are at business-case stage except the National Rehabilitation Centre, which is in design.

Cohort 3

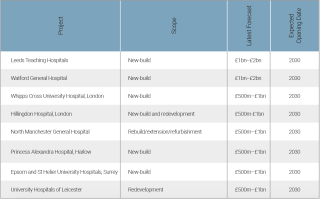

Eight schemes expected to complete construction by mid-2030

Cohort 4

Fifteen schemes: eight expected to complete construction after 2030

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk