At a glance our latest Top 100 suggests an industry in fine fettle. Overall orders and profits at the leading contractors are up on a year ago, but a closer look shows a sector under stress.

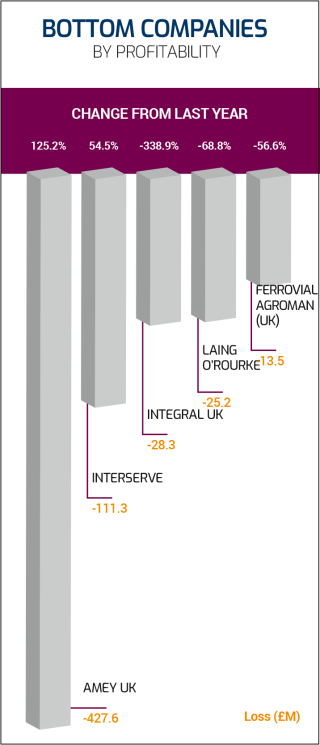

Total turnover at the Top 100 this time was £72bn, which is 4% higher than last year at the same companies. The industry’s 10 biggest contractors generated revenue of £33.1bn, which, at 46% of total revenue for the Top 100, is the same as a year ago.

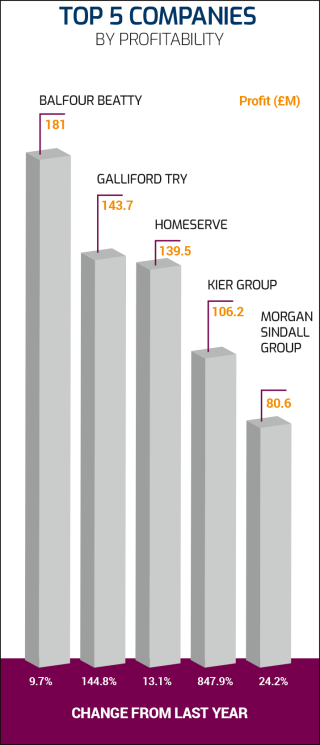

Those same 100 companies generated pre-tax profits of over £1.1bn, which is also 4% up on a year ago but both these positive headline figures mask some big issues.

Turnover retreated at three of the top 10 contractors: Balfour Beatty, Interserve and Laing O’Rourke. Out of the top 100 companies, turnover grew at 66 companies. In last year’s Top 100, 77 companies grew revenue, which suggests growth is being stunted.

Turnover – as the old City adage has it – is mere ‘vanity’ and profit is the true measure of business ‘sanity’. And this year, a plethora of red marks in the profit column of the Top 100’s latest accounts is enough to test the sanity of any finance director.

The biggest deficit came at Amey whose parent group, Spanish company Ferrovial, is selling its UK subsidiary. That decision is not surprising as Amey was hit by losses of £428m in 2018 from a disastrous highways deal in Birmingham and problems in the waste and utilities sector.

Two other top 10 contractors, Interserve and Laing O’Rourke, also slumped to crushing losses. Overall, 13 companies in the Top 100 traded at a pre-tax loss in their latest financial year. Twelve of those companies also traded at a loss in the previous year. But losing money isn’t the only story.

Profitability is under pressure. Of the latest Top 100, 48 companies either traded in the red or suffered from reduced profitability at a pre-tax level, and it would appear that it is the smaller players who are feeling most pain. Only three of the top 20 contractors by turnover suffered reduced profits or losses.

National contractors, such as Interserve, Costain, Galliford Try and Kier, have all alarmed investors by issuing profit warnings over the past year. Unlike a year ago, when Carillion’s loss left a gaping hole in the Top 100, the remaining big players have all survived; but they are unrepresentative of the industry as a whole, which is losing companies at an increasingly alarming rate, with insolvencies on the rise.

Welsh outfit Dawnus was ranked 76th by turnover in the 2018 Top 100 but went bust in February. Birmingham-based Shaylor was in 97th spot a year ago but collapsed this summer.

Outside of the Top 100 several familiar regional names have gone under during the past year. They include Bolton-based Forrest and Scottish firms Havelock Europa and Crummock. Britain’s oldest contractor, West Country firm R Durtnell – which could trace its roots back to 1591 – collapsed in June. Pochin’s – another well-known regional name, followed in August.

In the period between the industry coming out of recession in 2010 and the end of last year, the construction industry of England and Wales has lost a staggering 28,000 companies according to data from the Insolvency Service.

The same month that the industry lost its oldest contractor, the IHS Markit/CIPS UK Construction Total Activity Index recorded the biggest drop in activity in a decade.

With Brexit uncertainty hovering over the wider economy, some clients are holding back on investment and main contractors with large workforces are coming under pressure.

“As a first step, stressed companies need to establish a cash culture and stable capital position,” says business consultant EY (formerly Ernst & Young), which has recorded a dozen companies in the FTSE Construction sector issuing profit warnings over the past year.

“Every construction business also needs an understanding of its problematic and vulnerable contracts so they can take prompt action. But, to create a sustainable business, it’s vital to establish stronger negotiating discipline, combined with closer management and better management information. This should limit the number of onerous contracts and the impact of problems that arise through the life of the contract,” adds EY.

A steady flow of contractors has left the stock market in recent years, including Amco, Metnor, Tolent, Styles & Wood and, in March this year, Interserve, when the group’s lenders took control.

There is little appetite from the City for contracting. In October 2016, piling specialist Van Elle raised £40m by listing on the junior Alternative Investment Market (AIM) only to issue a profit warning in July 2019.

There are now just 15 companies in the latest TCI Top 100 with a UK stock market listing and the decline in their aggregate share prices illustrates the industry’s reduced standing (see The TCI Share Index). Away from the heat of the City, companies can take a different view and focus on the long-term.

“Privatisation has proved transformational for our business,” says Paul Cossell, chief executive officer at ISG, which delisted in 2016 after being acquired by US investor Cathexis.

In 2018, turnover at ISG grew by 30% and profitability ballooned 201% to £27.4m. Cossell adds: “Taking a longer term perspective and investing in our business and, most importantly, in our people, has set the conditions for three years of record financial performance, and we are now the UK’s 24th largest privately owned company.”

ISG was in fact the third-highest ranked contractor in the 2019 edition of the Sunday Times Top Track 100 of the UK’s biggest privately-owned companies. The list included nine more contractors: Laing O’Rourke (18th place), Mace (23), Wates (37), Willmott Dixon (39), M Group (52), Bowmer & Kirkland (70), Sir Robert McAlpine (78), Graham (95) and Robertson (98).

Contrast that with the UK’s richest business people or families. According to the Sunday Times’ latest Rich List, the wealthiest contractor is John Kirkland and his family in 242nd place. There are no other contractors in the top 300 (see The Construction Rich List).

Were the Sunday Times to compile a Top 100 of the UK’s biggest privately-owned companies ranked by profit or by margin, the table would look very different.

In the latest TCI Top 100, 19 companies improved their profitability (or, in the case of Interserve, reduced its massive losses) on reduced turnover, among them first-placed Balfour Beatty and other leading industry names including Wates, Multiplex, BAM Construct and Sir Robert McAlpine.

The average profit margin in the Top 100 rose to 2.7% from 2.1% a year ago as 55 companies boosted this key financial measure.

Welsh contractor Watkin Jones has the best profit margin at 15%, ahead of Homeserve on 13.9%. But both companies eschew traditional contracting in favour of a development-led approach or smaller jobs.

For more mainstream main contractors, there is a shift to becoming more selective. To continue that old City adage, while turnover may be vanity and profit sanity, cash is reality. Poor cash flow is what has sunk many companies in recent years.

According to the Insolvency Service, 10,211 building contractors in England and Wales went bust between 2010 and Q2 2019 but that masks a wider cull being felt by their supply chain.

The impact on the supply chain from the failure of Carillion and other medium-sized contractors is evident in more Insolvency Service data, which shows that the biggest losses – 60% of all insolvencies in England and Wales since 2010 – come from specialist contractors.

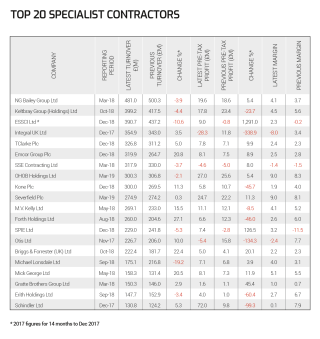

The Sunday Times Fast Track index does not include any specialist contractors and there are only 19 specialist firms in the latest TCI Top 100. Eight suffered reduced turnover in the latest financial year and three traded in the red. The average profit margin at the leading 20 specialist contractors is just 2.4%, down from 3.5% a year earlier.

This reflects the difficulties in a supply chain struggling with different payment codes and trapped when main contractors get into disputes over contracts, which are, on average, taking longer to resolve (research by Arcadis shows that the time taken to resolve a disputed contract has risen 28% to 12.8 months).

The losers, says Rudi Klein, chief executive at the Specialist Engineering Contractors’ group (SEC), are the supply chain. “There’s no doubt it’s getting tougher,” he says. “A major problem is the dire finances of the major and not-so-major contractors.”

Shaylor went down owing £17m to subbies due to what administrators FRP Advisory described as “severe cash flow pressures.” Dawnus went down owing around £40m to its supply chain, while Forrest’s unsecured creditors stand to lose £28m.

The impact of these failures can ripple out for years. Klein adds: “When a big firm goes down, some specialists will survive but they are just crawling along. Their growth is stunted for three, four or five years to come. They cannot invest as they have to maintain cash flow; but these are the businesses that take on apprentices and buy machinery.

“The impact over the next few years is potentially devastating,” says Klein. While Build UK, representing main contractors, is in favour of abolishing cash retentions, the SEC is calling for the introduction of project bank accounts in which retention monies can be ring-fenced to protect the supply chain in the event of a main contractor going down.

But Klein is dismissive of the government’s introduction of the Prompt Payment Code, which requires contractors to pay 95% of monies within 60 days. Big names such as Balfour Beatty, Costain, Interserve and Laing O’Rourke have been named and shamed but, says Klein, legislation already requires payment within 30 days.

With main contractors being more selective over work to boost profit margins and a supply chain under stress, what does the future hold?

The Construction Products Association (CPA) predicts that total construction output will fall 0.3% in 2019, and revised its forecast of growth for 2020 down from 1.4% to 1.0%.

Construction research group Glenigan expects the underlying value of project starts to fall 1% this year, but anticipates work in logistics premises, build-to-rent, student accommodation and social housing, secondary education and civil engineering to improve – but with a key proviso.

Allan Wilén, Glenigan’s economics director, says: “This outlook for the industry is critically dependent upon the eventual realisation of a Brexit agreement and the planned transition period. A no-deal Brexit would have a disruptive impact on the UK economy and construction activity”.

The CPA also says civil engineering work is essential and predicts that construction output would fall 1.7% in 2019 and experience no growth until 2021 without major infrastructure projects such as HS2.

While the failure of Carillion and other smaller main contractors continues to ripple out, the impact of Brexit could be the defining factor of the next Top 100.

Note: The comparisons made in the text are against figures from the previous set of results, which may – due to the timing of Company’s House filings – be different to the ones used in last year’s Top 100. Rankings may also differ from a year ago as the previous year’s figures are restated to include the absence and the inclusion of other companies.

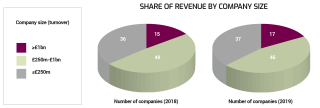

Profit warnings

Profitability for companies quoted on the Stock Exchange is under greater focus than ever and the number of construction firms warning about lower earnings is at a 20-year high.

In 2018, one in six quoted companies issued profit warnings, which was the second-highest level since the end of the last recession. These travails continued into this year with construction increasingly under the spotlight.

Contracting giants Costain, Galliford Try and Kier have all issued profit warnings this year. Research from business advisor EY shows that 29% of the firms in the FTSE construction sector cautioned over lower profits in the 12 months to June 2019. That is the highest level since 1999.

“PMI [purchasing manager index] data suggests that the UK construction sector contracted in Q2 2019, with activity in June falling to the lowest level for more than a decade,” says EY. “Tellingly, purchasing activity and new orders fell sharply, with Brexit and more general political uncertainty remaining high on the construction agenda.

“Our profit warning data reflects this rapid drop in activity. Of the 11 sector profit warnings issued in H1 2019, eight came in the Heavy Construction sub-sector, which contains main and sub-contractors. Three quarters of these profit warnings cited contract delays or cancellations.

“This hiatus comes at a time when high profile restructurings have already highlighted the sector’s deep-rooted structural weaknesses. Confidence in the construction industry is ebbing.”

The first quarter of 2019 saw the highest number of profit warnings for a decade. The total of 89 warnings was well above the 72 warnings made in the post-credit crisis period of Q1 2009.

The first quarter of this year also saw companies in the FTSE Construction sector issue the highest number of quarterly profit warnings since Q3 2016. “Protracted uncertainty is taking its toll,” said Alan Hudson, EY’s head of UK&I Restructuring.

“The ‘no deal Brexit’ countdown was especially disruptive for businesses exposed to blows to consumer, corporate and investor confidence — as well as those reliant on cross-border EU supply chains and regulation. Services and construction sectors both contracted in March’s purchasing manager surveys,” said Hudson.

In the second quarter of this year, overall profit warnings dropped to 69 but there were six warnings in the construction sector, which was the highest level for two decades. The most recent quarter saw five warnings from construction companies.

Looking ahead, EY advises that better understanding of problematic contracts and cost reductions may be the solution to reduce the number of companies warning on profits.

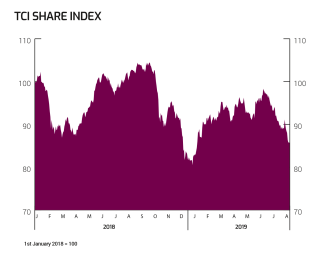

The TCI Share Index

Shares in contractors quoted on the UK stock markets have slumped by nearly 15% since the start of last year according to exclusive research for The Construction Index.

While companies such as Royal BAM’s UK subsidiaries and the UK arms of Bouygues, Skanska, and Vinci, are owned by groups listed overseas, in the latest Top 100 there are just 15 companies with exposure to contracting quoted on the British stock markets.

An index of their combined shares created exclusively for The Construction Index by Datastream shows how investor sentiment for shares in contractors has crumbled since the collapse of Carillion at the start of 2018.

The index rallied last autumn after positive results from some big UK contracting plcs posted more positive results. But by the end of 2018, the TCI index was down by nearly 25%. Despite a brief rally, the index was down a further 15% by the summer of 2019 after Carillion collapsed in early 2018.

Source: Datastream. The companies on the TCI Share Index are: Balfour Beatty, Costain, Galliford Try, Henry Boot, Homeserve, Keller, Mears, Morgan Sindall, NMCN, Renew, Severfield, Sureserve, TClarke, Van Elle and Watkin Jones.

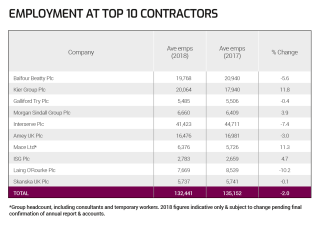

Staff and wages

As construction growth has faltered, the number of people employed by the UK’s biggest contractors is also in decline.

The 10 largest companies in the latest TCI Top 100 employ more than 130,000 people in the UK and overseas, but this figure is 2% below last year’s figure.

While some top 10 firms – namely Kier, Morgan Sindall, Mace and ISG – took on more staff, the average workforce fell at the six other leading companies.

At Galliford Try and Skanska UK these falls were marginal, but with profit margins under pressure, some big players took steps to cut costs last year.

Balfour Beatty took action to reduce total global staff costs by nearly 4%, while Interserve and Laing O’Rourke looked to mitigate losses by cutting the staff costs by 5%.

In contrast, ISG moved to invest in its workforce and staff costs rose by 13% in 2018.

ISG also has the most productive workforce with every employee generating an average of £804,000 in turnover. It should be noted, however, that a third of ISG’s workforce is based overseas in lower wage economies such as Asia.

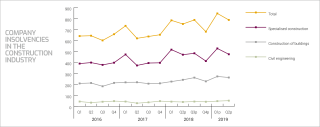

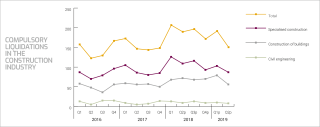

Insolvencies

The number of failing construction companies is spiralling as Brexit uncertainty hits spending.

Construction insolvencies had begun to drop off as the industry emerged from the worst of the last recession, but company failures have grown since the Brexit vote.

In the 12 months to Q2 2019, a total of 3,100 construction companies fell into insolvency, which is up 10% on the same period a year ago and 19% worse than two years earlier.

Eddie Williams, an insolvency specialist and partner at Grant Thornton, says: “In common with all industries, construction is getting worse. Insolvencies generally are going upwards but construction is going up at a slightly greater rate.

“There’s been a high degree of uncertainty and contractors operate on low margins. The challenge is liquidity: construction is a sector where payment and liquidity are as important as profit margins.

“This is all investment related,” continues Williams. “For some areas of the construction industry, uncertainty relating to the investment in new buildings is the problem.”

There has been a 16% rise in the number of building contractors in England and Wales falling into insolvency in the past 12 months. Between 2010 and Q2 2019, 10,211 building contractors in England and Wales went bust according to the Insolvency Service.

There are fewer civil engineering contractors in England and Wales but this cohort lost nearly 1,400 companies over the same period, with an 11% surge in the last 12 months.

The biggest losses have come amongst the specialist construction trades, where 18,452 companies have slumped into insolvency since 2010.

Between 2010 and the end of last year, more than 2,800 electrical contractors failed, while finishing trades lost nearly 1,900 companies and 1,400 plumbing, heating and air-conditioning specialists also disappeared.

Last year, insolvencies rose across nearly all specialist trades. The rise in electrical insolvencies did slow to 3%, but there was a 34% surge in the number of floor and wall covering contractors going under and joiners going down leapt by a quarter.

The only reduction in insolvencies in a specialist trade last year was in the demolition sector, which, as a possible indicator that more work could be about to start, offers a glimmer of hope as Brexit uncertainty continues.

The construction rich list

Building things isn’t perhaps the best way to earn megabucks, but 28 individuals and their families have managed to secure a place among the UK’s 1,000 richest people this year.

John Kirkland and his family remain the richest people to have derived their wealth from contracting and other construction-related work according to the most recent Sunday Times Rich List.

The annual survey shows that Kirkland, chairman of Bowmer & Kirkland since 1976, and his family have wealth of £585m but the growth in their worth is slowing as the construction industry is hit by economic uncertainty.

In 2017, the Kirklands’ wealth grew by £105m and the family rose 44 places to 242nd spot in the Sunday Times Rich List. Last year, this growth slowed to £55m and the Kirkland family stay in the same position.

House-builders and other people associated with the wider construction industry are growing their wealth at a faster rate than people whose riches are tied up in low-margin contracting.

Among the Sunday Times ’ 100 richest people in the UK, there are only two who derive most of their wealth from the construction industry: JCB owner Lord Bamford and housebuilder John Bloor.

Lord Bamford is again the person with the most wealth from the construction industry. With riches estimated at £4.19bn, up from £3.6bn a year earlier, Lord Bamford climbs two places to 33rd position on the Sunday Times Rich List.

John Bloor, who owns not only the housebuilding company that bears his name but also the Triumph motorcycle business, rises five places to 78th after his wealth increased by £54m to £1.91bn.

Buoyed by government support through help-to-buy, housebuilders fare well in the Sunday Times rankings. Redrow founder Steve Morgan is ranked in 158th position with wealth of £950m, while the McCarthy family – owners of Churchill Retirement Homes – control wealth of £650m.

The eponymous family behind plumbing supplier John Guest are £225m better off after selling the business to Reliance Worldwide Corporation for more than £687m last summer, but the Kirklands are the only contractors in the top 300.

The Lagan family are the highest new entrants, in at 308th position with wealth of £440m after selling their cement, quarrying and aggregates business to Breedon Group to focus on their housebuilding arm, Lagan Homes.

Another family with Irish roots, the Murphy clan, are five places behind the Lagans with wealth of £426m from their contracting and property operations, while Ray O’Rourke and family have broken into the top 400.

The highest new entrant in the top 1,000 by a family of contractors is that of Cormac and Patrick Byrne, the owners of Ardmore, in 703rd position.

While contractors are still growing their wealth, the rate of increase is slowing compared to other business and some are struggling to improve.

The McAlpine family fell out of the top 500 a year ago and have now plummeted out of the top 600 after their wealth failed to grow at all last year.

Fred Story & family also tumble down the rankings after their wealth shrank, while Michael Conway and family drop out of the top 800 as they are also worth less.

Amongst the new entrants to the Rich List are Stepnell owners Mark and Tom Wakeford and the owners of two specialist contractors, MGF boss Michael O’Hara and Brian Morrisroe of concrete frame firm AJ Morrisroe.

The highest-ranked boss of a specialist contractor is Raj Manak, owner of cladding firm Stanmore, at number 867. But Manak is worth less than he was this time last year, reflecting the difficulties reverberating down the supply chain.

Overall, there are 28 people that have derived their wealth from contracting amongst the UK’s 1,000 richest and only three suffered a reverse in their fortunes.

The wealth of the 20 richest construction families has increased to just under £4.9bn compared to £4.6bn a year ago, bearing out the old adage that, even in uncertain economic times, money goes to money.

Tarmac gets building again

Tarmac may be a name synonymous with building materials, but in years gone by the company was a major contractor and is increasingly returning to the fray.

Founded in 1901 after the discovery of the substance that gave the business its name, Tarmac floated on the stock exchange in 1922 and went on to build Britain’s first motorway and a swathe of other roads projects for Margaret Thatcher’s government.

Anglo American bought Tarmac in 1999 for £1.2bn, and the contracting operation demerged as Carillion with the materials operation retained.

Later acquired then offloaded by Lafarge, Tarmac is now owned by Irish materials conglomerate CRH. And besides its role as a leading materials supplier, Tarmac also builds, surfaces and maintains around 30,000km of roads annually.

This area of the business is growing rapidly. Last year, Tarmac was a major beneficiary in a £3.3bn road pavement framework set up by the Highways Agency, landing a package worth around £1bn.

Contracting work has also been boosted by acquisitions. In May 2017, Tarmac snapped up JB Riney, which earlier this year replaced Kier as Harrow Council’s maintenance contractor in a £110m five-year deal.

The JB Riney takeover was followed by the acquisition of Welsh civil engineering contractor Alun Griffiths in January last year in a deal later valued at £35.6m.

The Competition & Markets Authority subsequently launched an investigation into the acquisition but cleared the takeover last July.

Combined turnover of the last available accounts for Riney and Griffiths from 2017 are £226m. Tarmac’s 2018 accounts, which were not at Companies House when TCI went to press, should show the business becoming a major contracting force once again.

This article was first published in the September 2019 issue of The Construction Index magazine (magazine published online, 25th of each month.)

UK readers can have their own copy of the magazine, in real paper, posted through their letterbox each month by taking out an annual subscription for just £50 a year. Click for details.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk