Oh dear. Just when we thought construction had shaken off the worst of the troublesome ‘legacy’ contracts from the recession, the past year showed that many of the industry’s big names still have plenty of issues to work through.

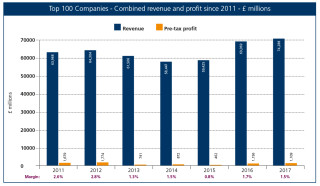

At first glance, the picture does not look too bad. Total revenue for all firms in the TCI Top 100 2017 was up 7.6% to £74.3bn (£69.1bn).

However, collective pre-tax profit dropped 4.1% to £1.1bn (£1.2bn), and the margin also fell, from 1.7% to 1.5%.

Some 34 firms recorded falls in turnover, 12 dropped into the red, and another 28 saw their profit fall.

And it’s at the top of the table where the biggest and most alarming casualties are found.

| Latest Rank By Turnover | Latest Rank By Profit | Company | Latest Turnover (£m) | Previous Turnover (£m) | Change (%) | Latest Pre-tax Profit (£m) | Previous Pre-tax Profit (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 49 | Balfour Beatty | 8,683.0 | 8,444.0 | 2.8 | 8.0 | -199.0 |

| 2 | 1 | Carillion | 5,214.2 | 4,586.9 | 13.7 | 146.7 | 155.1 |

| 3 | 94 | Kier Group | 4,211.0 | 3,275.9 | 28.5 | -15.4 | 39.5 |

| 4 | 99 | Interserve | 3,685.2 | 3,204.6 | 15.0 | -76.4 | 79.5 |

| 5 | 9 | Morgan Sindall | 2,561.6 | 2,384.7 | 7.4 | 43.9 | -14.8 |

| 6 | 98 | Amey UK | 2,531.0 | 2,531.9 | -0.0 | -43.9 | 23.6 |

| 7 | 100 | Laing O'Rourke | 2,513.2 | 3,127.4 | -19.6 | -245.6 | 12.4 |

| 8 | 2 | Galliford Try | 2,494.9 | 2,348.4 | 6.2 | 135.0 | 114.0 |

| 9 | 97 | Mitie | 2,126.3 | 2,231.9 | -4.7 | -42.9 | 96.8 |

| 10 | 40 | Mace | 2,041.1 | 1,811.3 | 12.7 | 10.7 | 36.2 |

Click for full table: TCI Top 100 2017

Balfour Beatty has squeezed back into the black with a slender £8m profit – a wafer thin margin of just 0.1% - after its annus horribilis a year ago which led to a loss of £199m.

This time round it’s Laing O’Rourke that is ranked bottom of the table on profit thanks to a £245.6m loss. And many other big names fare little better, with Interserve (ranked 99th), Amey (98th), Mitie (97th) and Kier (94th) not far behind the loss-making Laing O’Rourke.

But first to Balfour Beatty. Chief executive Leo Quinn, like all incoming bosses who answer a crisis call, wisely turned all the skeletons out of the closet after his appointment in late 2014. He then launched his ‘Build to Last’ plan in a bid to turn the business around. That didn’t help last year’s results, but this time round Quinn can justifiably claim that his strategy is working now and his company – the UK’s biggest construction group – has returned to profitability.

The firm posted only a marginal increase in turnover, up 2.8% to £8.7bn (£8.4bn), but Quinn is concentrating, wisely, on margin over growth. Balfour’s UK construction business returned an underlying profit from operations in the second half of the year and the situation continued to improve in its 2017 interims with revenue for the first half of this year up 6% to £4.2bn and a pre-tax profit of £12m.

Quinn said: “These results demonstrate the transformation being driven by focusing Balfour Beatty relentlessly on its chosen markets and capabilities. Profitability is rising, backed by positive cash flow from operations. Under stronger leadership and much improved bidding disciplines, the businesses are booking new orders at improved margins and reduced risk.

“The transformation of Balfour Beatty is well underway. We have returned the group to profit and significantly exceeded our Build to Last phase one targets.”

The company is now into Build to Last phase two – a 24-month period to the end of 2018 – when Quinn expects its UK construction business to be making “industry standard” operating margins of between 2% and 3%.

If Balfour Beatty is now out of the woods, then Carillion has just entered them. The firm’s full year results were, admittedly, not at all bad: revenue was up 13.7% to £5.2bn (£4.6bn) though profit dipped 5.4% to £146.7m (£155.1m).

But then came July’s bombshell. Chief executive Richard Howson stepped down after the company announced an expected contract provision of £845m was required to cover problem projects.

The size of the provision threatens to capsize Carillion’s construction operation completely, which reported revenue of £2.2bn in 2016. In last year’s Top 100, we noted how the firm’s decision to downsize its construction business by one third during the recession had seemed a judicious one when compared to Balfour Beatty’s travails. But that didn’t take into account the scale of the problems affecting some of its contracts. Some £375m of the provision relates to the UK business, chiefly three public-private partnership (PPP) schemes.

Philip Green, non-executive chairman, said the board was undertaking a “comprehensive programme of measures... aimed at generating significant cashflow in the short-term [and] a thorough review of the business and the capital structure.”

On an interim basis, Carillion will be led by Keith Cochrane, a former Weir Group chief executive. But at the time of writing, it looks as if the firm will need a super-charged ‘Build to Last’ of its own just to survive.

Kier sits third in the TCI Top 100 table thanks to last year’s impressive 28.5% increase in turnover to £4.2bn (£3.3bn). But the group’s usually reliable business model dived into the red to the tune of £15.4m (2015: £39.5m profit).

The firm blamed the loss on a £35.6m provision for problems in its Environmental Services business and £23.1m for the closure of Caribbean operations, plus the ongoing integration of the Mouchel business it acquired two years ago. In its interims in June this year, Kier said this reorganisation would result in a charge of some £73m in its next full year results, though its underlying profit would be “in line with expectations”.

Kier has also been troubled by a loss-making waste-to-energy joint venture, Biogen, in which it sold its stake during April 2017. But Kier’s problems in this sector are nothing compared with those of Interserve.

In February, Interserve announced a £160m charge, the cost of exiting the waste-to-energy sector, having had its contract on the much-delayed Glasgow Recycling & Renewable Energy project terminated by client Viridor in November 2016. The day before the contract was terminated chief executive Adrian Ringrose announced he would be stepping down in 2017.

The problems over the Glasgow waste-to-energy project resulted in Interserve posting a £76.4m loss last year (2015: £79.5m) though revenue increased 15% to £3.6bn (£3.2bn).

The firm’s construction operation, which accounts for £1.4bn of turnover, caused further headaches for Ringrose. It dived £2m into the red in the first half of 2017 (2016 H1: £4.5m profit) on revenue of £536.2m (£468.3m).

Ringrose said: “In construction, the continuation of a long period of challenging market conditions, coupled with areas of underperformance in operational delivery, resulted in a small loss for the division. We expect the restructuring and cost reduction measures we have taken in recent months to benefit the division’s performance during the second half of the year."

On 1st September, Ringrose handed over the reins to his replacement Debbie White, former chief executive of facilities management company Sodexo.

Morgan Sindall bounced back into the black in 2016, posting a profit of £43.9m (2015: £14.8m loss) on turnover up 7.4% at £2,561.6 (£2,384.7m).

The group’s construction arm continues to struggle with profitability, with a margin of just 0.7%, but that was compensated for by strong performances in its fit-out businesses Overbury and Morgan Lovell, which recorded a 4.3% margin, and Partnership Housing where the margin was 3.1%.

With first-half profit for 2017 up 45% at £23.5m, chief executive John Morgan expects full year results to be “significantly ahead of previous expectations”.

Amey experienced a disappointing 2016, posting a pre-tax loss of £43.9m (2015: £23.6m profit), mostly due to a £77m loss from its highways business. Group turnover was flat at just over £2.5bn.

In March the firm appointed a new chief executive, Andy Milner, who launched a cost-cutting drive. Milner said in a statement that 2016 had been a challenging year, “but we have created a stable platform with improved transparent, accountability and performance, increasing our opportunity for future growth and success”.

Amey’s highways business, which made an operating loss of £70.2m before exceptional items on £542m of revenue, has been reorganised with local authority and national road works now serviced by the same division.

Laing O’Rourke’s fall from grace was partly down to the investment made in its much-vaunted “design for manufacturing and engineering” (DfMA) strategy.

The firm’s huge loss for the year to 31st March 2016 was faced head-on by chairman Ray O’Rourke. He said: “It is with humility that I have to report our first loss in 15 years of trading as Laing O’Rourke. The genesis of this deterioration in profitability is rooted in the fact that coming out of a recession that had a negative impact over some six years (2009-14), it would have been difficult to avoid the severe headwinds our industry has endured through this period, which drove margins down to painful levels, alongside revenue reductions.”

O’Rourke said the post-2010 austerity measures introduced by the UK government “had a big impact” on the firm’s forward order book in health, education and military accommodation, on which he based his investment decision in the company’s DfMA manufacturing facility at Steetley, Nottinghamshire.

Laing O’Rourke’s UK business made a pre-tax loss of £141.3m on turnover of just over £1.1bn, with £26.6m in exceptional costs on contracts involving its offsite prefabrication plant, although losses were down on the three ‘first generation’ DfMA contracts which had led to write downs of £34.2m in the previous year.

O’Rourke said the company was set to return to profit for the year to March 2017 on anticipated revenue of £3bn.

He added: “We have continued to invest in our people, manufacturing, digital technology and engineering excellence, based on our firm belief that this is the future; I am pleased to say we continue to believe in this strategy.”

Galliford Try, despite turning in the best performance and margin in the top 10 this year, has recently been hit by substantial costs on legacy contracts in similar fashion (though not on the same scale) as Carillion.

In May, the firm announced it faced £98m of non-recurring costs, 80% of which relates to its share in two major infrastructure joint venture projects in Scotland – the £790m Queensferry Crossing and the £550m Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route.

Chief executive Peter Truscott said: "The impact of the legacy projects in construction, in particular the two large infrastructure projects, is regrettable. However, Galliford Try is no longer undertaking large infrastructure jobs on fixed price contracts. There are no other similarly procured major projects in our current portfolio and we are encouraged by the performance of the underlying portfolio of newer work.”

Galliford Try’s profit was up 18.4% to £135m (£114m) in the 12 months to 30th June 2016 with revenue rising 6.2% to nearly £2.5bn (£2.3bn). Significantly, this yielded a margin of 5.4% (4.9%).

Despite the legacy problem contracts, Truscott said he expected to deliver “a strong performance over the full year” when the firm’s next results are unveiled.

Mitie is included in this year’s Top 100 despite having exited contracting a year ago, in theory to stay on the more reliable terrain of support services. Despite this, the company has found the going pretty hard even in this supposedly less volatile sector. For the year to 31st March 2017, the firm announced a £42.9m loss (year to March 2016: £96m profit) on turnover down 2.7% at £2.1bn (£2.2bn).

Mitie has announced a major cost-cutting drive, making 3,000 of its nearly 60,000 strong workforce redundant in the 12 months to March.

Meanwhile, the auditing of the outsourcing firm’s results by Deloitte is to be probed by the UK's accountancy watchdog, the Financial Reporting Council.

Completing the top 10 is Mace, which was not immune to the problems plaguing its peers.

Pre-tax profit was just £10.7m in 2016, down 70% from £36.2m the year before, though turnover was up 12.7% at £2bn (£1.8bn).

Mace executive chairman Stephen Pycroft said that 2016 had been a “challenging” year. “A small number of our projects were, for a variety of reasons, harder to deliver than first envisaged,” he said. Problems included, “high risk projects, incomplete designs and a reliance on the performance of our construction partners”, he added.

Pycroft said: “2016 has taught us some very valuable lessons and as a result, we have put in place additional measures to prevent these problems happening again.”

Most of the other majors produced steadier financial performances during 2016 in contrast to their much larger rivals.

Skanska grew revenue 21.3% to £1.7bn (£1.4bn), though profit – which it is reporting in the UK as an operating figure – slid to £35.1m (£42.1m).

Costain’s turnover was up 31.2% to £1.7bn (£1.3bn), with profit climbing to £30.9m (£26m).

Wates, in its first full year results since acquiring Shepherd Construction, grew revenue more than a quarter to pass £1.5bn (£1.2m), with profit growing by a similar amount to £35.5m (£28.1m).

Willmott Dixon experienced a disappointing dip in turnover to £1.2bn, down 7.6% on the preceding year, though its profit recovered substantially to £31.1m from just £4.4m in 2015.

BAM Construct went past the £1bn turnover mark, and more than doubled turnover to £26.2m.

The two major Australian-owned contractors that operate in the UK both had good years. Multiplex, which has dropped the Brookfield part of its name, posted revenue of just over £1bn, a two-thirds increase on the previous year, though profit was down more than a fifth at £16m. Lendlease’s revenue also surged, by 71.3% to £898.7m, while profit rose to £66.7m after the disappointing £5.5m reported in the previous period.

Vinci and Sir Robert McAlpine both recovered from the losses made in 2016. Vinci returned a £2.8m profit on turnover of £931.7m after losing £69.4m the year before; Sir Robert McAlpine made a £10.2m profit on £869.6m of revenue, having lost £35.7m in 2016.

The financial strife in this year’s table was largely confined to the big boys, though a handful of the medium-sized players also ended up in the red.

John Sisk made a pre-tax loss of £17.9m, despite growing revenue 22% to £419.4m. The 2016 results for Bouygues UK have not yet been filed, but its figures for the previous year show a £19.4m loss on turnover of £349.6m. Byrne Group, which has experienced problems with its fit-out arm Chorus, reported a loss of £11.9m on £329.4m of turnover.

Diversification – the share of revenue in the UK’s biggest construction groups

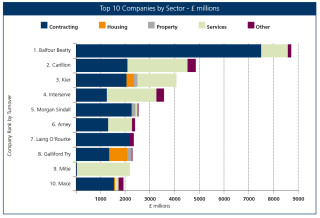

Construction companies are rarely purely contracting operations. Most of the top players have within their groups various different operating businesses which they have bought and sold fairly regularly over the past two to three decades, usually according to the whim of the market.

In the early ‘90s, development was the fashion, though now only Kier, Galliford Try and Morgan Sindall have property businesses. Kier and Galliford Try are also the only major players to hang on to a house-building business; the UK’s top private house-builders are now mainly standalone operations.

Come the new millennium and support services became the fashionable option for those wanting to diversify. It was a trend driven largely by the requirements of bidding for PFI projects.

Support services also offered steadier margins, usually around the 4% mark, compared to the more volatile construction industry. That partly explains why most of the big players have hung on to their facilities-management arms. Another factor was the perceived benefit of being classified on the stock market under ‘support services’ rather than ‘construction’, which is the case with Carillion, Interserve and Mitie. The latter has now almost completely wound down its contracting business.

During the past 10 years some construction groups began expanding their design and engineering capabilities, notably Balfour Beatty with its acquisition of Parsons Brinckerhoff in 2009. The idea was to provide a ‘one stop shop’ to serve all of a client’s built environment needs. That era came to an end when Balfour sold Parsons Brinckerhoff to consultant WSP, though it was briefly courted by Carillion which said it saw value in the ‘all under one roof’ approach.

So why, particularly in view of the slim margins offered by construction (discussed in the Revenue & Profit box), does contracting still have appeal in construction’s boardrooms?

The big attraction of the business is the up-front cash it provides. Unlike, for example, support services where the money is paid out over the term of the deal, construction provides contractors with most of the cash up front. This enables the likes of Kier and Galliford Try to move money across into their house-building and development arms, where profit returns are greater, and top up the overall group margin. It’s not a bad model. But after the troubles that have affected the UK’s top contractors in this past year or so, a few firms may be reviewing their strategies.

Margin call – how much profit can contractors realistically expect?

The low margins of the construction industry have long vexed its bosses.

Historically, contracting operations have rarely done better than 2%, and often much, much less. Construction groups have looked to other subsidiary businesses to provide an overall boost to profit and margin, usually house-building, development, support services, design, plant hire or a combination of all or some of them.

In this year’s table, the margins do not make for pretty reading. The overall figure stands at 1.5%, down from 1.7% last year, and certainly not showing the post-recession boost that may have been expected as contractors flush out ‘legacy’ problem contracts.

However, the situation gets even uglier with scrutiny of the top 10. With half of these firms in the red, they posted a collective pre-tax loss of £79.9m, on total revenue of £36.1bn.

As with last year, when Balfour Beatty’s £199m deficit cast a big red shadow over the top of the table, this time round another major player – Laing O’Rourke – has posted a huge loss of some £245.6m. Interserve, Amey, Kier and Mitie all dived into the red, while problem contracts at Mace slashed its profit by 70% to £10.7m.

And next year, the full impact of the £845m of provisions that Carillion announced last month will have damaging effect on the industry’s overall margin.

Meanwhile, in the background, construction industry output is starting to fall, while rising inflation and input costs threaten to erode what little margin there is.

Against this backdrop, there have been some surprisingly ambitious noises from contractor bosses about increasing their margins.

An emboldened Balfour Beatty CEO Leo Quinn, with wind in his sails after putting the company back in the black, is aiming for a margin of up to 3% next year. A number of firms are even talking bullishly about pushing for a 5% margin.

Interestingly, Morgan Sindall chief executive John Morgan, has set a “medium-term target” for his construction business of 2%. Morgan has been on the firm’s board since 1994, so it might be safe to assume that he knows a thing or two about what a realistic construction margin is.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk