The fact that BIM stands for ‘building information modelling’ gives a clue that it might not always be ideal for use on bridge projects. Constructing bridges differs in many obvious ways from buildings (as well as in some less obvious ones) and this has traditionally meant the use of ‘workarounds’ to tailor BIM systems for this application.

However, both the sector as a whole and some individual software companies have been stepping up efforts over the past couple of years to address the specific needs of bridge designers, contractors and owners. In tandem, use is growing of the term BrIM to distinguish systems specifically for bridges from their more building-focused counterparts.

A fast-tracked international initiative has recently produced bridge-specific ‘industry foundation classes’ (IFC), standardised, digital descriptions that enable data exchange across a wide range of hardware devices and software platforms used by owners, designers, suppliers and contractors. They incorporate details of objects such as columns and slabs – their types and attributes including materials and properties, locations and so on.

More abstract information such as costings can also be included, as too can details of the parties and processes involved in installation and operation. The final version of the IFC-Bridge extension was published as an official draft in May.

Trimble is one of the companies that has been upping its focus on bridges. The ‘I’ for ‘Information’ is at the core of both BIM and its sibling BrIM, says Päivi Puntila, business development director at Trimble Solutions. The data is the key aspect to focus on and the model serves as a 3D view of that data, she says.

Data needs to be standardised in order to be of use and to ensure that any changes are reflected across the model so that everything remains up to date.

Software inevitably evolves over time – even a few years can be a long time in terms of compatibility with previous versions. The issue is compounded for bridges, as they may have a target life of 100 years or more. This makes it particularly important to use an open format not linked with particular software or a particular incarnation of that software, especially as keeping the bridge in good repair tends to be a public safety issue.

Puntila welcomes the recent publication of the bridge-specific IFC as it will enable owners and all the other participants to start using BrIM to an open standard. “This gives an opportunity - regardless of what software the different participants are using – for them to access and share information,” she says. The building industry has been showing the way for infrastructure to follow. As a result, take-up for bridges will be much faster than it has been for buildings, she predicts.

One of the differences between bridges and buildings is that bridges are usually owned by a public authority of some kind, such as Highways England, Network Rail, Transport Scotland or a local authority. Even a private sector concession operating a major crossing for decades doesn’t usually take on the actual ownership. “Buildings get bought – a building doesn’t necessarily have the same owner for its whole life,” Puntila points out.

She sees owners as playing a crucial part in the digitisation and transformation of the industry, once they get to appreciate the use of digital data in preference to drawings. A particular challenge is the way that traditional project types are budgeted and organised. “It’s easy to say that you want to collaborate, but when you have design-bid-build there isn’t really any connection between the design office and the contractor so everything goes through the owner.”

With design-build projects, the basic idea of ‘we’re in this together’ comes in from the start. Engineering offices are aware of the contractor’s requirements from the outset – rather than only after the data is there and the requests for information start coming in.

Owners will have other requirements – they need to be asking themselves how they can make use of the bridge’s digital data in future maintenance. These days, detailed digital models can also be generated from surveys of existing structures, enabling owners to include older bridges as well as new ones in their digital registers and compare results from one inspection to the next.

BrIM has the potential to transform the bridge maintenance industry by enabling the creation of accurate registers of all the structures. Much of this information is currently held on microfilm, observes Puntila – and such records are not updated. “If the bridge is 50 years old then the drawings are 50 years old – and a lot has happened to the bridge during those years,” she says. She wants owners to appreciate the benefits of digital information. The term ‘digital twin’ is increasingly being used in connection with data that is a true reflection of the structure, including the ability to be updated to incorporate changes through its life beyond the original as-built record.

The data needs to be shared, both with participants in the bridge’s design and construction and – increasingly – with machines, whether within a fabricator’s workshop or for controlling earthmoving equipment on site. “That’s why the standardisation is so crucial,” says Puntilla. This is especially important now that a lot of construction is prefabricated, with a move to assemblies that are made off site.

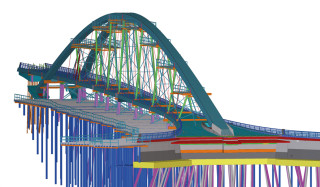

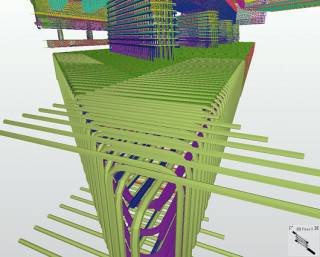

Two years ago, Trimble decided to develop a focus on the bridge design and construction market, including owners’ needs. Its 3D modelling software, Tekla Structures, already included features relevant to bridges as well as buildings, such as support for the detailing of rebar. The company was aware of bridge departments – in Finland, Sweden and Norway in particular – that had already been using it on their projects, even though it wasn’t created with bridges in mind.

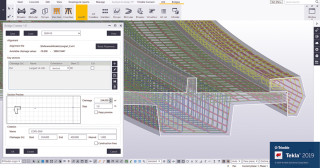

The new focus resulted in this year’s launch of Bridge Creator, an extension to Tekla Structures to address issues that are specific to bridge projects. Road alignment in particular is one of the big challenges for bridge designers, as it can change frequently in the early phases of design. Bridge Creator allows users to import data directly from road design software, create key sections that define the deck or abutments and then carry out modelling and detailing of the rebar while adapting to any changes. Difficulties in modelling double-curved bridge decks are now a thing of the past, says Puntila.

Tekla Structures is a ‘parametric’ modelling tool; each object – a pier for instance – has parameters that define its properties, such as its geometry and relationships with other parts of the structure. For instance, if the position of a column is moved, then the others can be made to move as well. An object can be cloned and a subsequent update can then be applied to all instances of that particular item.

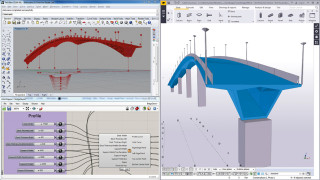

Designs can be created from scratch by using Tekla Structures and its new Bridge Creator extension. The system is also compatible with modelling the bridge’s form by using the intimidatingly-named approach of ‘algorithmic-enabled parametric design’ – or ‘parametric design’ for short. All this really means is using visual programming tools to simplify the creation of complex forms, which can then be managed and changed where necessary.

The Grasshopper plug-in for Robert McNeel & Associates’ Rhinoceros 3D design software is a popular example. This type of design, along with integration of the model with structural analysis programs, does however require a different way of working. Once someone has shown interest in the straightforward programming that is involved in parametric design, they tend to become their firm’s ‘internal guru’ - but take-up expands once colleagues discover how useful it is, finds Puntila.

Combining parametric design with a suitable BIM tool can be used to produce information-rich data that can be used throughout the project’s life, from managing changes and finding clashes through to asset management.

Trimble Connect is the company’s collaborative system. It can be set up right at the start of a project, irrespective of what other software is being used, as it’s based on open standards.

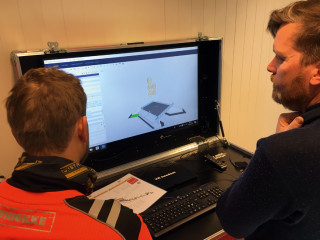

Today’s systems have been developed to make model views easier for reading on site – for instance, by someone fixing rebar, who may have no need or interest in seeing other parts of the model. “For all software providers, when we move to site with the BIM or BrIM models the usability and user interfaces need to be completely different than for the engineers’ offices where this whole BIM world started,” says Puntila.

Norway is a leader in the move towards model-based processes, with multiple bridge projects under way where the work is being done without any drawings having been produced.

Data updates, comments and so on can all take place within the same environment, with all parties using the same system but supplied only with data that is relevant to their role, whether they’re building the foundations, fixing rebar or setting up scaffolding.

Norway’s Directorate of Public Roads is the authority responsible for verifying and approving the design of all national and county road bridges before erection is allowed – normally approving approximately 300 structures per year. It decided to allow designs to be submitted using BIM and by doing this it is providing a platform and preliminary guidelines for the industry to evolve its use of information models. Experience acquired through the verification process is being used to refine the guidelines.

The introduction is proving successful and there has been rapid adoption. Work in this area only began during the summer of 2017 and by November 2017 there were two small structures undergoing verification. But by late June 2019 there were 67 structures pending verification, 75 undergoing verification and 40 that had been approved.

The first Norwegian bridges where engineering consultancy Sweco worked without drawings were on the E6 highway on a project built by Veidekke Entreprenør. Veidekke engineer Jasmin Zecic says that the company is using the technology on a total of 43 structures on the new E6 highway from Arnkvern to Moelv. Challenges include getting used to working in this way and that extra people are needed to provide support to others.

Sweco is currently working on the Randselva Bridge, a seven-span concrete box structure more than 630m long that will form part of the E16 highway. The project involves a partnership between PNC as the main contractor, Isachsen as groundwork contractor and Sweco and Armando Rito as the design team. Tekla software is being used for 3D modelling of the form and reinforcement, with Grasshopper and Rhino for parametric design. Most of the official delivery is done by IFC-files.

BIM – or BrIM – is allowing the engineers to create 3D simulations that contain significantly more information on the actual structures than drawings produced using a traditional computer-aided drafting system.

Sweco BIM developer Øystein Ulvestad finds many advantages in the new approach, including better understanding of the scope for contractors, faster production of the design and of revisions, precise extraction of quantities from the model and more efficient clash controls.

However, there are also some challenges, such as the very different way of doing quality control, a need for further standardisation, the difficulty of showing any objects that have been removed from the model and the need to ensure that written information is transferred well.

It has long been possible to view and collaborate on projects modelled in 3D by gathering round a large screen – or wearing VR headsets. This is leading to the setting up of site ‘kiosks’ on Norwegian projects, where people can go to view the model from different perspectives. These larger screens are being used to augment the tablets or phones used to access the data while on site.

Individual businesses may start by using BrIM or BIM internally, reaping benefits in terms of their own efficiency and the quality of their work. But operating this way within a kind of silo doesn’t spread the benefits across the whole project. “My main message is that owners need to wake up,” says Puntila – who believes that the best way to wake them up is to let them see the benefits for themselves. “No-one will request it if they see only benefits for those working for them.”

This article was first published in the July/August 2019 issue of The Construction Index magazine

UK readers can have their own copy of the magazine, in real paper, posted through their letterbox each month by taking out an annual subscription for just £50 a year. Click for details.

Got a story? Email news@theconstructionindex.co.uk